Photo, above: In the San Xavier District, the striking silhouette of the San Xavier Mission church rises against the August monsoon sky, a guiding reminder of intermingled Tohono O’odham cultural and spiritual traditions. The “White Dove of the Desert” (the church), is acclaimed for its intricate 17th Century Baroque construction and is built of adobe, which has stood resilient like the Tohono O’odham Himdag (way of living in the world). Credit: Mary C. Wilson.

Author’s note: As a Tohono O’odham tribal member who has helped plan tribal environmental policy, administer research and public health programs and contracts, I was amazed when I read the Fifth National Climate Change Assessment (NCA5), a federal document that reported on the Indigenous holistic worldview and used the word “spiritual,” throughout Chapter 16, Tribes and Indigenous Peoples (see NCA5 Key Message 1; Heath Risks). It’s a big deal for Indian Country! This is a sign that the U.S. Federal government is starting to understand and include the important non-linear spiritual aspects of Indigenous communities in their climate science and environmental health policies. Including these spiritual and other cultural views in the NCA5 is a long-overdue acknowledgment of the complex ways Indigenous peoples connect with their homelands and cultures. It’s a step toward understanding the holistic approach that has helped Indigenous communities survive and stay strong for generations.

The Tohono O’odham Himdag (way of living in the world) challenges the way climate science thinks by highlighting how important non-linear spiritual and other cultural considerations matter when developing Indigenous climate strategies. The Tohono O’odham holistic approach is based on ancient traditions and Tribal rights. As the need to mitigate the impacts of climate change becomes ever more urgent, ancient traditional ways of living have kept a steady pace in the race against time. These holistic strategies have led to strong and effective solutions for dealing with climate change. The good news is that the Tohono O’odham of southern Arizona and northern Mexico have continued their traditions to create climate strategies that really include everyone, making them more effective.

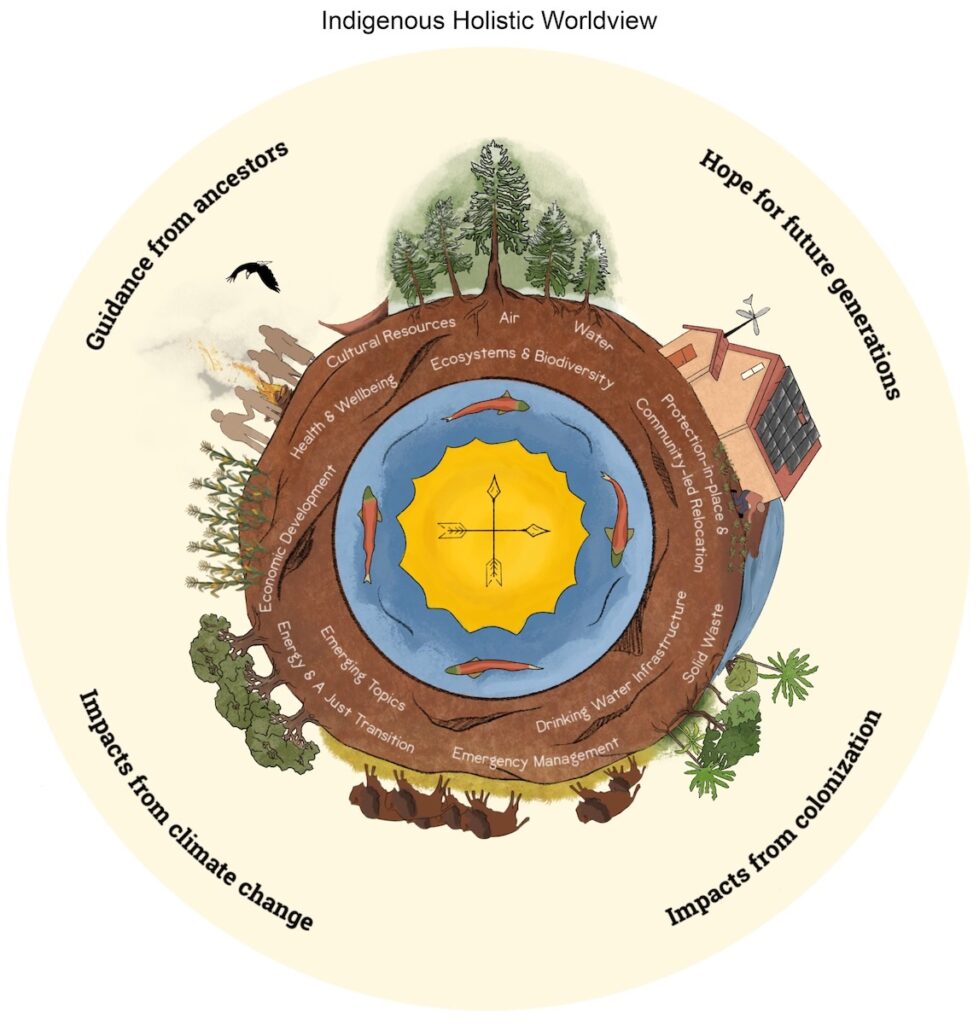

Indigenous holistic worldviews offer diverse and complex expressions of climate change. This image demonstrates interconnected drivers of sustenance, climate change impacts, and future aspirations. Illustrations connecting human social systems and the environment, including the relationship between social justice (e.g., colonialism, racism) and environmental change (e.g., ecological degradation, pollution), represent certain Indigenous approaches to climate change. Figure from the Fifth National Climate Assessment, ©STACCWG 2021. Used with permission.

Many Indigenous people, including the Tohono O’odham, are like environmental researchers; they understand the complexity of how everything in nature and supernature are connected. For many generations, the Tohono O’odham have built their own unique strategies to resist changes in climate and have incorporated culturally focused strategies into their government constitutions and policy mandates. Uniquely, the Tohono O’odham of southern Arizona and northern Mexico are very aware of any changes in the environment by closely observing monthly and annual cycles in nature, noting how plants and animals interact with one another.

The Tohono O’odham communities’ interpretations of their Himdag’s ceremony, language, story and song are site-specific. I am from the Cedagi Wahia community, where we have specific creation stories that occur on a specific land base. My homeland is at the end of the Baboquivari Mountain Range, in northern Sonora, Mexico. This story presents my critical understanding of the Tohono O’odham Himdag as an example of a multi-faceted Indigenous holistic worldview.

-Mary Cathleen Wilson

San Xavier Co-Op Fields, Santa Cruz Valley, August 2023. Photo: Mary C. Wilson.

Amid the generous sprawling semi-desert landscape of the San Xavier District, just south of Tucson, Ariz., the San Xavier Co-op Farm stands as a testament to the enduring commitment to the Tohono O’odham’s healthy farming practices. Spanning across this resilient Native American community, the Co-op’s fields are a brilliant tapestry of traditional crops, which include beans, melon, and squash, along with ground mesquite beans, and dried cholla buds—all tended with diligence and reverence.

The farm’s store is a hub where locals and visitors alike gather to purchase these sustainably grown goods, each product embodying the spirit of the Tohono O’odham homeland and the food security legacy of the Tohono O’odham Himdag (way of living in the world). However, as the current climate change-induced megadrought intensifies, both the fields of San Xavier and the Tohono O’odham people who live here face unprecedented challenges.

San Xavier Co-Op Honey for sale. Photo by Mary C. Wilson.

San Xavier Co-Op Store “OPEN” for business with fields in the background. Photo by Mary C. Wilson.

Himdag: Wisdom for a Warming World

“Given to us as a gift from our Creator, our Tohono O’odham Himdag has endured through generations . . . In order for our Himdag to be carried on, we must care about our heritage and preserve the gift that was given to us since time immemorial. Therefore, our Tohono O’odham Himdag demands respect and maintenance by all who claim it.”

-Tohono O’odham Constitution Language Policy, 1986.

The Tohono O’odham Nation, located in southern Arizona and northern Mexico, has over 34,000 tribal members and a land mass covering 2.8 million acres. Approximately the size of Connecticut, the Nation shares 62 miles along the US-Mexico border, with 14 Tohono O’odham villages located in Sonora, Mexico. Here in the Sonoran desert, one of the hottest and driest regions of the North American continent, Tohono O’odham people have lived and farmed since time immemorial according to the principles of the Himdag.

Map of Tohono O’odham Nation lands. The Nation governs four separate areas of land, organized into 11 districts. 14 villages are located on the other side of the US-Mexican border, in Sonora, Mexico. Credit: Native Climate.

The Himdag is a fundamental concept embedded in the Tohono O’odham Nation’s 1986 Constitution. It represents a way of life that emphasizes interconnectedness, community, and respect for nature and supernature (sacred and spiritual beliefs that influence daily life). It is a holistic worldview, in which every element of life is interconnected, and respect for both the natural and spiritual realms are paramount. As a climate change strategy, the Himdag has been promoting sustainable living, conservation of natural resources, and resilience against environmental changes since time immemorial; it’s a climate adaptation model we’ve had all along.

This concept is in complete contrast to post-Renaissance European notions that saw the environment as a natural resource ordained by God for man’s sole benefit. This perspective has historically led to the commodification of natural elements and a separation of humanity from the environment. Conversely, climate science today is increasingly recognizing the value of Indigenous knowledge systems like the Himdag for their sustainable practices and deep ecological wisdom.

Today on the Tohono O’odham Nation, some people believe that the discussion of the Himdag is something they prefer not to participate in because it is very personal. On the other hand, many Tohono O’odham have chosen to protect and celebrate their heritage openly and have incorporated the Tohono O’odham cultural values and traditions of the Himdag into the Tohono O’odham Constitution, legislative policies, Himdag Ki: (Tohono O’odham way of living-house, a cultural museum), and the Tohono O’odham Community College’s Tohono O’odham Studies Associate of Arts degree.

The Himdag stresses harmony with the environment, cultural traditions, and the communities’ responsibilities, imparting the importance of sustainable practices and environmental stewardship. It encourages a balanced relationship with nature, fostering resilience to temperature changes through traditional knowledge and contemporary practices. As we delve deeper into this Tohono O’odham climate change adaptation story, we explore the merging of tradition and innovation, highlighting the critical importance of Himdag and climate action in preserving the legacy of the multi-faceted Tohono O’odham ways of living in the world.

Seeds of change

On a sweltering 107-degree July afternoon in Sells, Ariz., I heard the sound of crunching mesquite beans beneath my feet in front of the Kaij Ki: (Seed House). As I entered the store, my eyes were drawn immediately to the unmistakable blue label of the San Xavier Co-op logo on ½ lb. bags of ground Wihog Cu:I (mesquite flour). I use mesquite flour to make chocolate chip cookies and mesquite tortillas. Mesquite flour is high in protein and low in fat. Tohono O’odham farmers Jesse Garcia and Ju:Ki Patricio stood in back of the Kaij: Ki food store sales counter, and greeted me with their welcoming smiles and a big ‘Hello, are you Mary Wilson?”

The small store front shelves held packaged traditional foods that included tepary beans, dried Ha:l (O’odham squash), Ge’e Hu:ñ (June Dent corn), Wihol (split peas), and Pilkan (Sonoran Wheat). A Tohono O’odham woman entered the store and purchased a bag of Bawi (tepary beans); Garcia turned his head and greeted her with a quick, courteous nod. Later, while sorting dried squash seeds, Jesse popped a few in his mouth as a quick snack.

“Our store is a place where O’odham can get the real food, here at the real grocery store,” Garcia said.

Left to right: Tohono O’odham farmers Jesse Garcia of Cowlic Village, Garden Supervisor, and Ju:Ki Patricio of Ge Oidag (Big Fields), Youth Coordinator at the Kaij: Ki (Seed House), Center for Sustainable Agriculture. Photo: Mary C. Wilson.

Garcia, who is Garden Supervisor with the Center for Sustainable Agriculture’s Adopt A Sonoran Crop Program, farms in nearby reservation fields, and the Sells Hospital gardens. He is acutely aware of the delicate balance required to sustain crops in the region’s harsh conditions and has noticed changes in recent years.

“Over the last three years, the heat has really become noticeable, rains don’t come through, wildlife migrate to other areas,” Garcia said. “Changes are happening on this planet…It’s a new era. Last year I really recognized it because there were only two or three good rains. It was quite a shock!”

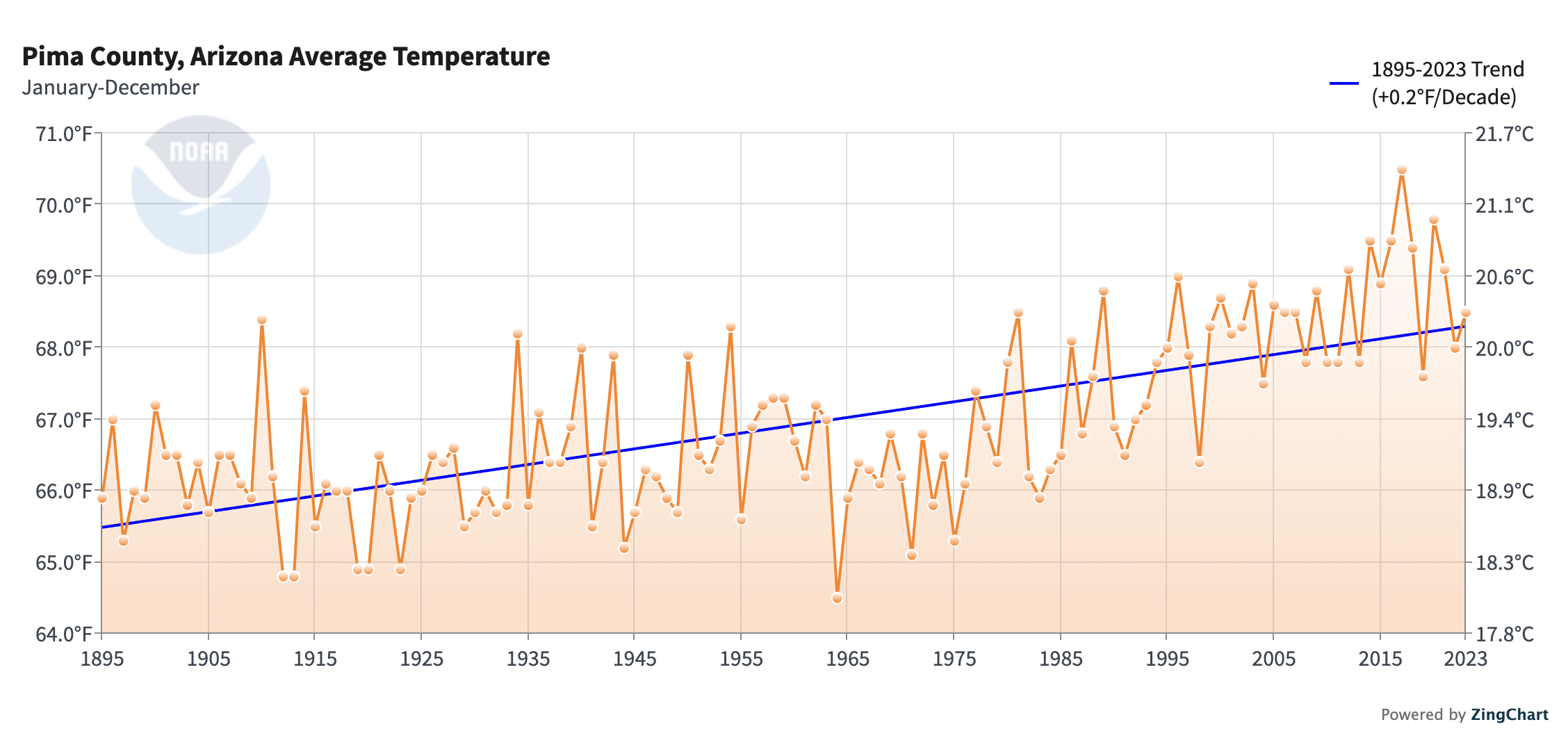

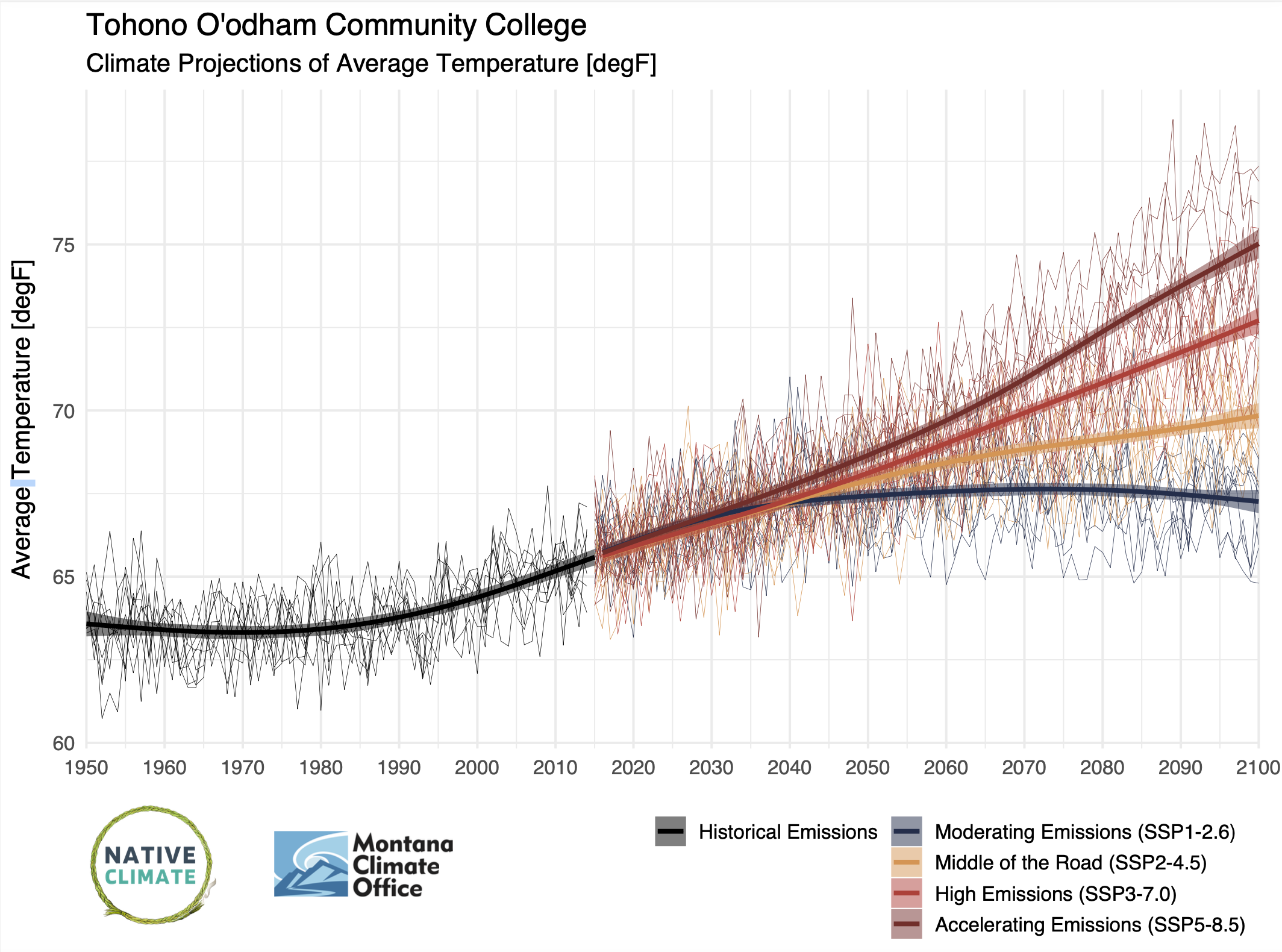

Over the past century, climate data shows that average year-round temperatures on the Tohono O’odham Nation (see Pima County average temperature chart, below) have risen by nearly three degrees. In the future, projections show that this trend is expected to continue. How much warming occurs depends largely on collective actions and decisions made by people from far beyond the reservation borders, but within the Tohono O’odham Nation, adaptation planning has begun.

Climate data from 1895 to the present shows that average annual temperatures on the Tohono O’odham Nation in Pima County, AZ have increased by nearly three degrees (F). Credit: NOAA/NCEI.

Climate records from 1950 to the present (in black) show that average temperatures on the Tohono O’odham Nation have increased by several degrees. Future projections (in colors) through the year 2100 show a range of possibilities, but additional warming is expected under all scenarios. Credit: Native Climate.

In 2018, the Tohono O’odham Nation published their first Climate Change Adaptation Plan. In it, author Selso Villegas recommended traditional and other innovative water use techniques and drought-resistant traditional crop varieties as essential adaptation tools. In addition to the written plan, Villegas went out into the community to spread the word among Tribal members about changes to come. These conversations were meaningful, remembers Garcia.

“When Selso Villegas from Natural Resources went out to teach the people about global warming, it opened my eyes to the bigger picture, how precious water is,” Garcia said. “It changed my whole perspective. Global warming is really happening. It is here, right now!”

In February of 2019, before the Subcommittee on Indigenous Peoples Oversight Hearing on The Impacts of Climate Change on Tribal Communities, former Tohono O’odham Vice-Chairman and current Chairman Verlon Jose discussed how climate change has brought about increased threats from heat, drought, and wildfires.

“With respect to addressing impacts from heat and drought, we have created a Nation-wide agricultural plan to attempt to ensure the survival of traditional foods and provide these foods to our members,” Jose said in his statement. “Measures include seed-banking of traditional plants, expanding food-crop acreage, finding better ways to get water to crops, and enhancing the Nation’s food-distribution infrastructure. The Nation has undertaken the long-term inventory and monitoring of wild food plants.”

“In addition, the day-to-day impacts of increased heat and drought on our members’ ability to gather and use traditional foods is staggering,” Jose continued. “The Nation has been increasingly creating and implementing programs to encourage O’odham people to return to a traditional diet in order to improve health. However, returning to a completely traditional diet is next to impossible because of the damage done to our traditional food sources as a result of climate change.”

Hot Days, Cool Buildings

With summer air temperatures that on average surpass 104ᵒ F and can reach 118ᵒ F; O’odham people are no strangers to the heat and have developed cooling strategies that could be adopted elsewhere.

Long before the Spanish brought European square-room adobe technology to the desert, the Tohono O’odham circular floor and rounded roof mud homes called Melhok Ki: (ocotillo and mud house), were constructed with a framework of wood and brush. Families like the Garcias of Cowlic Village have long used adobe mud brick construction as a resilient construction strategy to cool their homes, protecting them from severe heat.

“…the wind would come through the adobe house of my grandparents, and it was cool in their house,” Garcia recalled, his voice changing into a gentle peaceful tone as he pondered over the childhood memories of his family’s comfortable adobe dwelling.

In the Tohono O’odham Nation’s Baboquivari District, the District Office Complex construction illustrates responsible and sustainable building practices that align with traditional Tohono O’odham values and modern environmental considerations. Here, adobe construction and passive solar strategies act to reduce heating and cooling energy use. Adobe bricks have been proven to be affordable, durable for 400 years if maintained, and a natural building source that can be replenished faster than it can be used.

Another Tohono O’odham traditional cooling strategy is the use of the Watto, a ramada built out of mesquite logs and saguaro ribs or ocotillo branches. This traditional “cooling center,” gives relief from the heat of the Sonoran Desert, which receives only (eleven – NPS reference) three to 15 inches of yearly rainfall.

In a warmer climate, the value of these traditional cooling strategies is becoming increasingly evident, providing an alternative to the high electricity costs of other modern cooling methods.

In his statement to the Subcommittee on Indigenous Peoples, Tohono O’odham Vice Chairman Jose reported, “The heat, drought and fires put people, animals and food sources at risk — and impose greater costs on the Nation to ensure the well-being and safety of our people. For example, many of the Nation’s members used to open the windows at night to keep their homes cool. But with the hot temperatures extending long into the night our members now need to keep air conditioning units on throughout the day and night in order to keep the temperature in their homes at safe levels.”

“This results in increased electricity costs for individual members,” Jose continued. “The Nation also incurs additional costs as we work to ensure the safety of our members who may not be able to afford air conditioning units. Traditionally, to cope with intense daytime heat the O’odham people constructed Wattos—open-air shade structures with dirt floors, which we would wet throughout the day. As part of our Climate Change Adaptation Plan, the Nation is currently exploring a return to some of our traditional building practices in order to reduce the cost of air conditioning during the hottest months.”

San Xavier Wattos (Ramadas) made from hand-hewn mesquite logs and ocotillo branches are currently used by San Xavier food vendors. Historically, the O’odham people constructed these open-air shade structures, creating outdoor “cooling centers.” During the hottest hours of the day, the dirt floors can be dampened with water, giving even greater relief. Photo: Mary C. Wilson.

In the Tohono O’odham Nation’s Baboquivari District, the District Office Complex uses adobe construction and passive solar strategies to reduce heating and cooling energy use, combining traditional Tohono O’odham values with modern environmental conservation concerns. Photo courtesy of Selso Villegas.

As temperatures grow more extreme, new methods and materials are being put to work. The Tohono O’odham Nation’s climate change plan is strategically designed to work collaboratively with TON’s Emergency Preparedness resources to serve community members during climate-related natural disasters, such as extreme heat events.

During the summer of 2018, in what Jesse Garcia describes as “one of the hottest summers ever;” the Tohono O’odham Nation’s Emergency Preparedness division cracked on──opening more emergency cooling centers to shield tribal members from the severe heat.

Tohono O’odham Vice Chairman Jose noted, “Since the beginning of O’odham history, we have learned to live in the desert, and have adapted to high summer heat and scarce water. But as climate change has begun to disrupt both our traditional and modern ways of living, we have had to figure out ways to cope with these changes.”

“Tribal members suffer as hotter temperatures force a greater reliance on air conditioning, which leads to unaffordable electric bills.”

The New Normal is hotter and drier

Due to climate change, the abnormal megadroughts being experienced by Indigenous people of the southwest are becoming normal. By connecting the site-specific ways climate changes are affecting Indigenous communities, it is possible to understand how extreme weather, record-high temperatures, and heavy monsoon rains are happening more often. These personal revelations can help to convince everyone that climate change is real. As Garcia, the Tohono O’odham farmer, noticed, the heat isn’t normal — and it’s getting worse. With climate change making droughts more common, what Garcia considered an unusually hot day is more likely to happen on a normal basis. But it isn’t normal, and Jesse’s observations matter.

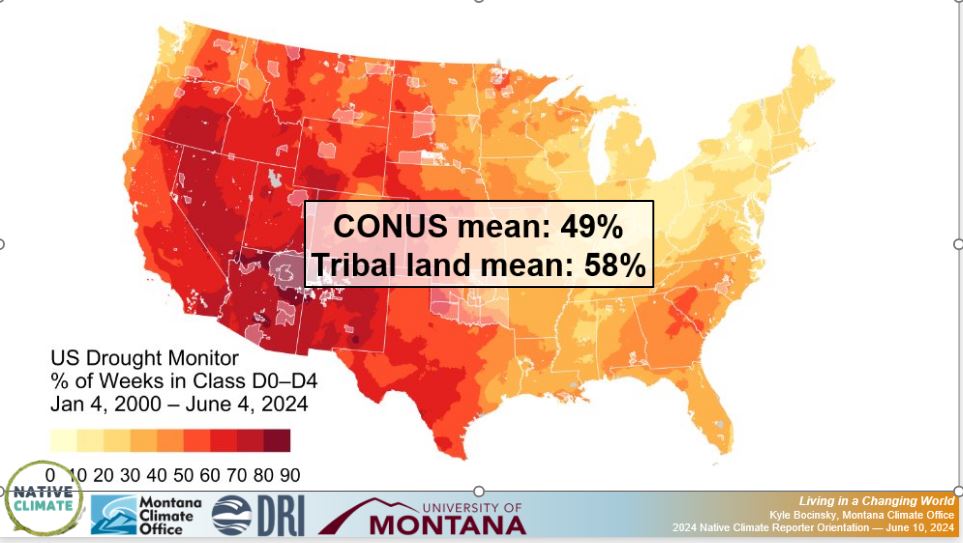

The new normal on the Tohono O’odham Nation is going to be even hotter than in the past — and also drier. Warming temperatures across the southwest are contributing to conditions of drought. The southwestern United States is currently experiencing a megadrought – a drought lasting more than 20 years. In addition, according to analysis by Kyle Bocinsky of the Native Climate Team, Tribes including the Tohono O’odham are being impacted by drought conditions at a higher rate than other portions of the US.

Tribal lands are being affected by drought at a higher rate than other portions of the United States. During the period from Jan 2000- June 2024, Tribal lands experienced drought conditions 58% of the time, compared to 49% across the entire continental US. The Tohono O’odham Nation, in southern Arizona, is among the hardest hit regions. Credit: Kyle Bocinsky/Native Climate.

To accommodate for increased drought, both the climate science and the Himdag perspectives recognize the need for adaptive water management. However, the Himdag’s approach is rooted in deep, place-based knowledge and cultural practices, while climate science often relies on more advanced types of modeling and technology.

A key principle of the Himdag is respect for all the elements existing in the natural world. Water is sacred and so the management of this vital life-giving source has been reverently harnessed by the O’odham for ages. Ancient O’odham, who were known as the Hohokam, propelled water through 12 ft. deep water canals, which connected into a system of smaller canals── spanning 500 miles. Today, members of the Tohono O’odham Nation are trying to revive some of their traditional techniques for farming the region’s dry landscapes.

Ajo Farmers Market mural at the Center for Sustainable Agriculture (CSA) in Ajo, AZ on a sweltering 115 F July afternoon. The CSA collaborates with the Tohono O’odham Nation on the Southwest Native Foodways Gathering, Tohono O’odham Youth Programming Group, and the Adopt-a-Sonoran Desert Crop, traditionally grown through “Ak-Chin” (mouth of the wash) dryland farming and partners with the Sells Indian Hospital Garden. Credit: Mary C. Wilson.

In Ajo, Arizona, Garcia is working with the Center for Sustainable Agriculture (CSA) to revive drought-tolerant crop species through their “Adopt-A-Sonoran-Desert-Crop” program and preserve traditional farming methods such as Ak-Chin dry land farming. The word ‘Ak-Chin” means at the “mouth of the wash,” and is a method that uses the rains harvested from floodplains, or washes to irrigate fields. These programs are growing in popularity, says Garcia.

“Basically, we harvest water from the monsoons, and we collaborate with the Native Seed Search by distributing traditional seeds,” Garcia explained. “We just went out to Menager’s Dam community, and we were only expecting a few people to be interested, but about thirty people showed up. We were surprised how this is catching on!”

For Garcia, working in these programs brings back memories of his own childhood experiences in his grandparents’ gardens. These experiences come with health benefits.

“Just like the elders in the communities, who have good memories of growing their own food to eat — when I was just a little kid, I experienced happiness watching the green plants grow in our family garden,” Garcia said. “I teach my own children now about growing our own healthy food.”

Climate Adaptation Takes a Village

Democracy by consensus is one of the ancient foundations of the Himdag and was used as a community outreach decision-making tool to develop both the 2018 Tohono O’odham Climate Change Adaptation Plan and a 2024 San Xavier Vulnerability, Resiliency and Site-Specific Climate Change Adaptation Plan, which is specific to the Nation’s geographically separated San Xavier District.

Consensus building involves sharing your ideas on any given issue and moving to agreement, and can build trust between O’odham leaders and their constituencies. It is this exchange of thoughts and ideas that a discussion can end up in a different place than where it first began.

Beginning with discussions in 2020, the long and tedious journey to gather tribal and academic support to develop the San Xavier District’s climate change research plan was eventually approved by both the University of Arizona’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), and the Tohono O’odham Institutional Review Board. The climate change research plan blended traditional Tohono O’odham democracy’s consensus-building model and modern participatory action research methods, which invited community members not just to participate but to invest their community values in discussions that made everyone feel respected. By ensuring that the San Xavier community climate change experiences and ideas were included in the earliest discussions and development of climate adaptation strategies, the collaborative mix of old and new information actively involved the community in a crucial collaborative outreach process. This grassroots research process respects traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) while working in concert with climate change science data-gathering methods.

This is how tribal adaptation planners became aware of concerns such as the changes in blooming times of important plant species, said Celestine “Sally” Pablo, Vice-Chairwoman of the San Xavier District. During these meetings, Pablo heard from the community that culturally important species like the Bahidaj (Saguaro Fruit) and Ciolim (Cholla Buds) were blooming irregularly.

“…Sometimes late, sometimes early, and this is one of the challenges our people face,” Pablo said.

The strength of listening to different points of view and incorporating community concerns into plans builds trust and respect as all views are validated. Listening respectfully to other points of view creates the opportunity for new, yet undiscovered ideas to hatch, and can lead to another way of understanding, which helps the discussion broaden and mature.

“We O’odham farmers know you need to adapt,” said Juki Patricio, Youth Coordinator for the Center for Sustainable Agriculture’s Farm Apprentice Internship Program. Patricio has farmed traditionally since youth, and in 2012, interned with the Tohono O’odham Community Action in Project Oidag (garden), which helped create reservation school gardens. Patricio would like to see more tribal members go out and learn about their land, and start learning about the plants themselves. Credit: Mary C. Wilson.

New Problems, Age-Old Answers

Climate change presents a significant threat to the transfer of traditional knowledge from one generation to the next. By raising awareness among our youth about the dangers of climate change to our Himdag, future leaders will continue to address environmental challenges and reinforce the importance of O’odham cultural food gathering practices. It is important to include younger generations in adaptation efforts – and in applying lessons from the past to present-day challenges.

The Himdag’s interconnectedness principle in effect serves as the cornerstone of Tohono O’odham environmental policy, effectively functioning as a climate change strategy aimed at protecting the homelands and all their inhabitants. By comparing the Himdag with climate change impacts on various environmental factors, we can better understand how traditional indigenous principles can inform and enhance current environmental practices.

The Tohono O’odham way of living in the world promotes the idea that in order to create climate change adaptation strategies you need to first and foremost embrace nature and supernature’s interconnectedness principle. By combining Himdag with modern climate change science strategies, both traditional ecological knowledge and cultural practices offer valuable lessons for present day environmental policy. The Himdag is Tohono O’odham’s enduring climate adaptation strategy. The Himdag is a timeless solution. The Himdag is an ancient answer to climate change.

For Further Reading

Ak-Chin Indian Community. Ak-Chin Farms. Ak-Chin Indian Community. Retrieved August 30, 2024, from https://www.ak-chin.nsn.us/ak-chin-farms/

Bernstein, A.S., S. Sun, K.R. Weinberger, K.R. Spangler, P.E. Sheffield, and G.A. Wellenius, 2022: Warm season and emergency department visits to U.S. children’s hospitals. Environmental Health Perspectives, 130 (1), 017001. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp8083

Central Arizona Project. Wa:k Hikdan – Bringing life back to the Santa Cruz Rive. Know Your Water News. September 20, 2023

Guida, D. Ben. (2015). Adobe Bricks: The Best Eco-Friendly Building Material. Advanced Materials Research. 1105. 386-390. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.1105.386

He, X. (2019). Droughts and Floods in a Changing Environment Natural Influences, Human Interventions, and Policy Implications (Doctoral dissertation, Princeton University). 56-61

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2019). Climate Change and Land. IPCC Special Report. pp. 45-47.

Meade, R.D., A.P. Akerman, S.R. Notley, R. McGinn, P. Poirier, P. Gosselin, and G.P.

Kenny, 2020: Physiological factors characterizing heat-vulnerable older adults: A narrative review. Environment.International,.144,.105909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105909

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2020). Climate Change: Global Temperature Projections. In National Climate Assessment. pp. 23-33.

Food and Agriculture Organization. (2020). Agroforestry practices and climate resilience. FAO Publications. pp. 34-36.

San Xavier Co-Op Farms. (2024). Mission Statement. sanxaviercoop.org

Seager, R., Ting, M., Held, I., Kushnir, Y., Lu, J., Vecchi, G., … & Cook, E. R. (2015). Causes of the 2011-14 California drought. Journal of Climate, 28(18), 6997-7022.

Tohono O’odham Nation. Valuing the Tohono O’odham Himdag, Tohono O’odham Community College, https://tocc.edu/himdag/

Tohono O’odham Nation. Associate of Arts Degree. Tohono O’odham Community College https://tocc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/2020-2022-UPDATED_AATS_79-80.pdf

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2008). Water Management in Agriculture. USDA Publications. pp. 18-24.

U.S. House of Representatives. (2019, February). Testimony of the Honorable Verlon Jose, Vice Chairman, Subcommittee on Indigenous Peoples Oversight Hearing on The Impacts of Climate Change on Tribal Communities, 2019. https://democrats-naturalresources.house.gov/imo/media/doc/VernonJoseTestimony02.12.19.pdf

University of Nevada. 2024. Crop Diversification. Extension | University of Nevada, Reno https://extension.unr.edu/publication.aspx?PubID=3816#:~:text=Crop%20diversity%20encompasses%20several%20aspects,a%20resilient%20agricultural%20cropping%20system

Williams, A. P., Cook, E. R., Smerdon, J. E., Cook, B. I., Abatzoglou, J. T., Bolles, K., … & Livneh, B. (2020). Large contribution from anthropogenic warming to an emerging North American megadrought. Science, 368(6488), 314-318.