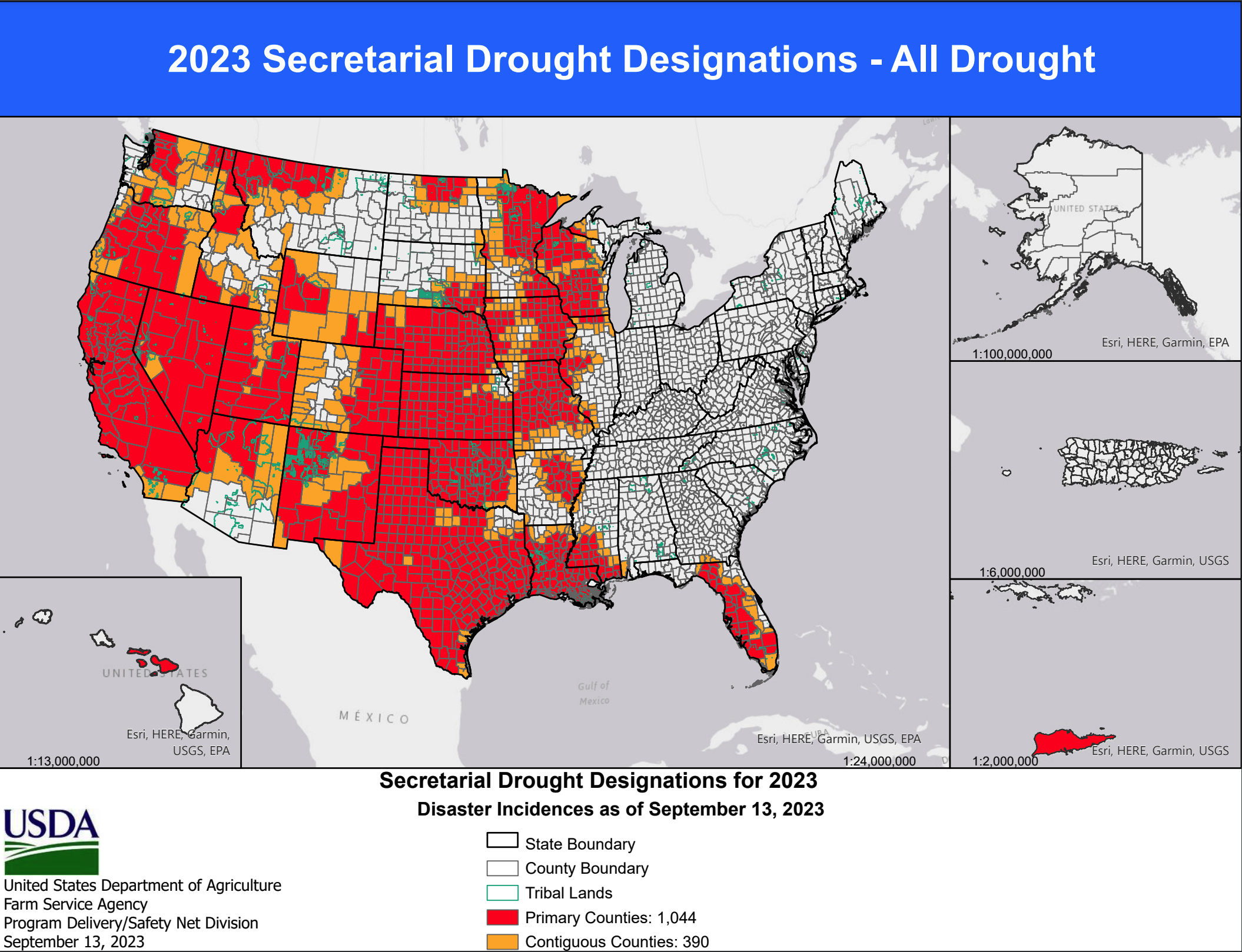

Author’s Note: The southwestern region of North America is experiencing periods of prolonged drought, expected to worsen in severity under future climate projections. The region is predicted to become more arid in future years, with a drought risk that will likely exceed even the driest centuries of the last millennium. The Southwest has experienced drought conditions for most of the past two decades. In 2023 the USDA has designated natural disaster areas across large portions of Arizona due to severe drought conditions.

These shifts in climate result in ecological and cultural shifts, as indicated by the agricultural-related natural disaster designations. Rural Native communities can be inequitably impacted by climatic events due to frequent position in isolated, harsh environments, dependence and relationship with biocultural systems, and other factors that affect the ability of people and communities to adapt such as limited financial resources, political marginalization, and unstable access to land and water.

Secretarial disaster designations for crop disaster losses, 2023. USDA.

These are some of the challenges facing Hopi Nation within these changing climates and increased droughts. Cultural Survival has called the mesas of northeastern Arizona where the Hopi homelands persist, “the final battleground for the survival of this ancient Tribe.”

In 2013 Elizabeth Kennedy Rhoades interviewed 35 Hopi elders, government employees, farmers, gardeners, and ranchers on the topic of drought to document Hopi peoples’ observations of drought and drought-impacts on way of life and culture. This was the first study to explore climate-related health impacts among a Southwestern Native community. The study found that drought and more variable weather patterns in the last 10-20 years were having adverse effects on cultural livelihoods including farming, gardening, and gathering that in turn have adverse impacts on diet, activity, and wellbeing.

Climate never stands alone, as a separate issue, within Native communities, but is entangled with ways of life, culture, and health. These challenges are compounded by the unjust use of Native lands and waters. For example, Peabody Energy used ~ 45 billion gallons of groundwater to transport coal from the Black Mesa coal mine (1960s – 2005) to a generating station in southern Nevada within its lifetime, leading to decreased underground aquifer capacity. Decreased groundwater access has already impacted farming practices and well levels. Full reclamation of the Black Mesa and Kayenta mines closed by Peabody Energy has not yet been completed. Hopi Nation is a modern battling ground for water and environmental rights, just as it is a rich source for ancestral knowledge on water stewardship.

In contrast to the mesas of Hopi in northeastern Arizona, I grew up and continue to subsist on the wet side of Hawaiʻi Island. Rain, or ua, as we know it in ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi, is an almost constant part of my life. The several trips that I’ve made to Arizona and Nevada in the past year have brought me to really think about cultural resilience and about Native communities that have long thrived in areas of low rainfall, like Hopi Nation. I believe that these lifeways, this ancestral knowledge, have much to offer contemporary approaches to water stewardship and care.

I recently met with Nadine Manuel, a Hopi elder, who has dedicated her life to the service of Native peoples, to talk about these connections between climate and culture within Hopi homelands. I first met Nadine through her son, Joe, who I was blessed to attend Stanford with. I have come to know Nadine as one of the most genuine, grounded people that I know, and I was very humbled to sit down with her over the phone to talk about climate and culture.

An Interview With Nadine Manuel

Gina: Can you start by telling me a little about yourself and your background?

Nadine: I was born and raised on the Hopi Reservation. My government name is Nadine Pongyesva. I’m from the Hopi Tribe in Northern Arizona and my maiden name is Hopi. Pongyesva. The meaning of my last name means to sit down to the altar. My married name is Manuel, so my name is Nadine Manuel currently. My name, Pongyesva, is from my grandfather, my dad’s father, who is from Hotvela, Arizona in the Third Mesa. My dad was from Third Mesa and my mother is from First Mesa. My clan is maternal. My mother is from the Mustard Clan and we call it Asa, and my maternal side of the family, we originally migrated from the Rio Grande Pueblos in New Mexico.

We lived up on the mesas and we didn’t have much and there were no cars. My grandfather always managed to have a car and so we always relied on him to, you know, do things for us and get, and we didn’t have running water. So, they had to use the 50-gallon water drums. They would go down to the windmill and put the water in the drum barrels and bring them back up on the mesas. And they did this for other people too in the village that needed water, they would come and ask if they could go get them water. So my grandfather and my uncle or my brother, my dad, they would go and get the water for them and you know, take it to their homes.

Gina: Thinking about climate and growing in Hopi culture, are there any key relationships that you want to share?

Nadine: I’m going to touch on Hopi weddings because the information that we’re eventually going to get to has a bit to do with the culture and how that’s going to work into the water situation. There are four stages to a wedding in Hopi culture. The first part is for the bride before she becomes a bride, she goes to the to-be-husband’s family with her aunts, which would be her paternal women and offers a meal to them. And that’s when the boyfriend’s family either accept it or they don’t. If they accept it, then there’s going to be a wedding.

The second part is when the bride takes piki bread, which is blue corn pastry paper thin bread, and the yeast bread, blue cornmeal, white cornmeal, and sweet cornmeal to the groom’s family. And she’ll be there at their residence for four days, sometimes up to two weeks, grinding corn for his family. While she’s grinding corn, the groom’s father and relatives will be in the kiva weaving the bride’s robes. When they finish, then she’s ready to go home and they dress her and her wedding robes and her dress and moccasins that are made for her while she’s grinding that corn. And then she comes home, and they bring her home with all the game, you know, meat products and groceries. They’ll bring her home with that. But before they bring her home, the bride’s parents will go to the groom’s home and take piki bread, cornmeal, and all that over in abundance. And with the abundance of food at both the bride’s home, and the groom’s home, they give that out to the relatives that helped.

The blue corn and the white corn, sweet corn, are all a very, very important part of the Hopi life. And if you have that, that’s considered wealth. And the reason why it’s considered very highly is because we don’t have irrigation. Just no water. We live in high desert area where there’s no, you know, rivers or ponds. We have a few springs, you know, in villages. But we don’t have any irrigation like running rivers and things like that. Lakes, we don’t have that. So, we panned rain and snow.

And everyone’s very happy when it snows a lot in the winter and if it rains a lot during monsoon and during the rain season, because then the water tables in the ground are a lot better for when it’s time to plant corn and they plant corn in, usually in the end of March or beginning of April. And they cultivate everything very, very carefully.

A field of Hopi corn. Credit: Robert Quotskuvya.

Gina: Without irrigation, how do Hopi grow corn?

Nadine: All the plants, the corn, are planted three feet in diameter from the other plants, because the ground water has to be there. And so, they have large cornfields out in Hopi. And they’ll plant the whole thing with corn. And it’s large because they have to plant them three feet apart in each direction. And then they have to make sure that if there’s more than one, plants in one hole that came up, they have to thin it out and leave only the strong ones. All because of the water.

Gina: That’s a lot of work.

Nadine: They also do a lot of praying and a lot of dancing and singing while they’re cultivating and planting. And you have to have a good heart. When you do that, you can’t have any negative feelings when you’re doing things like that. Each plant is dealt with personally and each plant gets a visit. They’re very dedicated to it. And so when the corn starts coming up, when the tassels will start, you know, coming out, they know that the ears are coming out, so a lot of the farmers will go and spend some time at their cornfields. Because they have to watch the birds. And any cattle that might come in, horses or anything like that.

Gina: Does your family still grow corn today?

Nadine: No, we don’t. My dad was a very, very good farmer, him and my grandpa. But once my dad left our farming just kind of stopped. My family doesn’t have any corn anymore and it’s kind of a shame on my part, because I should have had, or I could still have, my boys learn how to do it. My dad had taught my sister’s husband how to plant and how to do it, so he knows how. So my sister gets to have some corn every year from what he harvests. But it’s nothing like what it used to be. The harvest is very small. And it’s just because there’s no water.

“…it’s nothing like what it used to be. The harvest is very small. And it’s just because there’s no water.”

There’s been a lot of influences that caused that: planting and seeing anything grow, it’s not there anymore. Have you heard of a company called Peabody Energy? Yeah, the Hopi and Navajo tribes went into an agreement with them to have a coal mine on the reservation that was in a joint-use area. So, when that happened, when they were mining the coal, that company was using groundwater, the aquifer, from the ground to push that coal across country. So they were draining the land of water just to move their coal. So then the water table started to drop even lower.

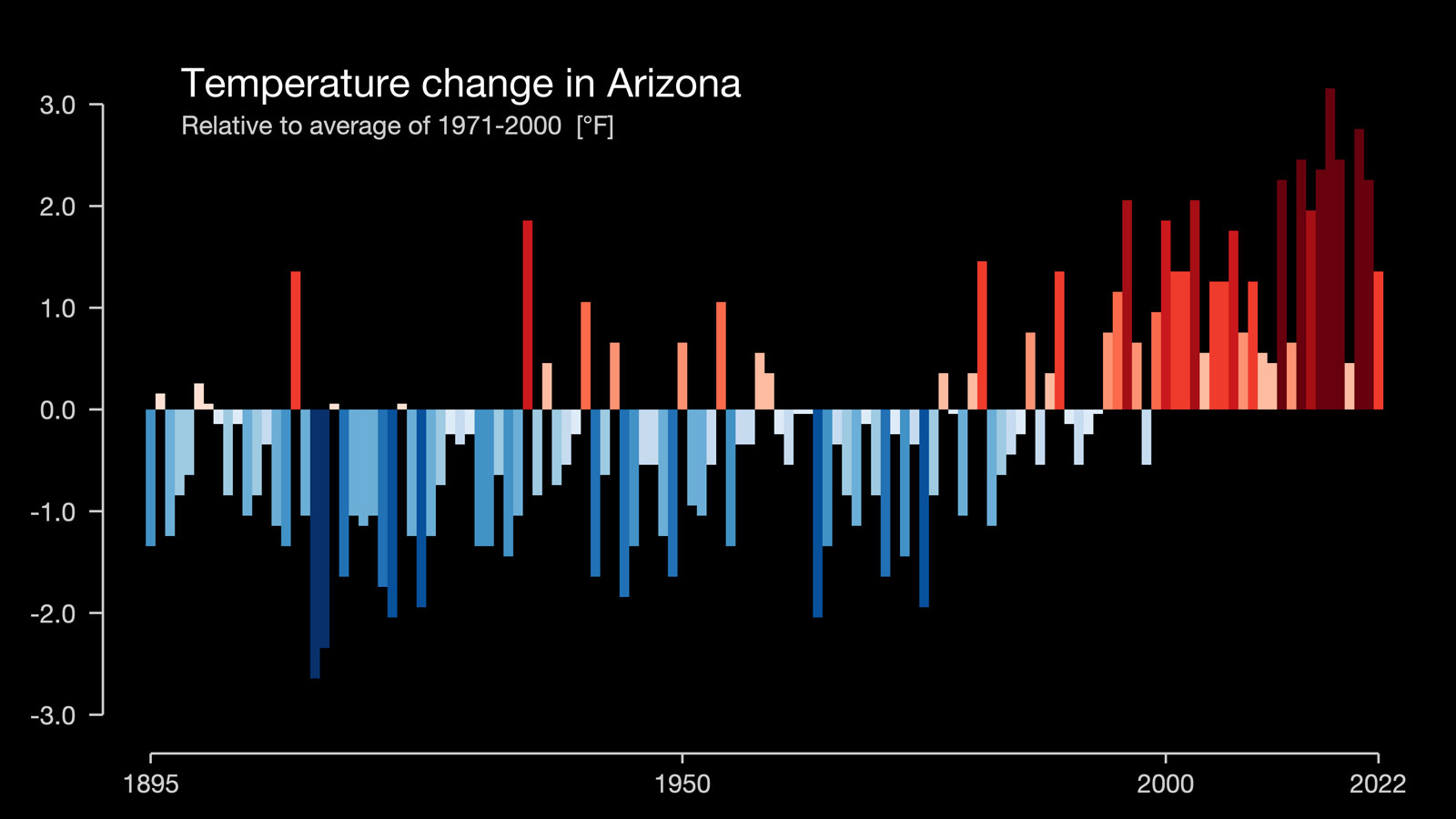

What used to be is not there anymore. So then, when the farmers plant they have to even go deeper. And then sometimes, because of climate change, because everything’s changed, there’s no abundance of snow, there’s no abundance of rain, you know, it’s very, very dry now. So all that that used to be is no longer there. It’s very hard to farm now. It’s even harder now to farm like that. Very seldom you’ll see somebody that really succeeds.

Gina: Has this affected ceremony or other cultural practices?

Nadine: No, it’s affected the whole thing. It’s affected the whole thing because there’s certain things that they use, the kachinas, from plants. Like the corn plant. When we grow corn plants and there’s certain things that happen during the growth, that they use certain parts of the corn for body paint or other things they use. It’s not there anymore. So now because of that they’re having to use other means of using other things for that purpose.

By July you have a harvest and it’s just in time for the home dance. That’s when the kachinas go home. And when the Kachinas come in July to dance, and come to the people, they bring corn in the morning. They have the full stock when they come, the kachinas and they give them to the people that have, you know, are watching the dance. And the kids will take the corn stalks that have corn on them and they go back to the house. And this is what we used to do. All of us would get some. They would give us with a little kachina doll tie on it. So we would have a little kachina doll that came with our corn. That was a part of our culture. That we had to believe in that, that it was magic when the kachinas gave you our corn that it will grow and make more.

Temperature change in Arizona from 1895-2022. Credit: Ed Hawkins/University of Reading.

Gina: Could you share anything more about that connection between spirit and climate?

Nadine: Oh yeah. Because, like I said, we don’t have water, so everybody has to be in prayer and there’s various times in our calendar where we have to humble ourselves and be quiet. And those are the times where people meditate. And those are the times that people are in prayer because we’re praying for water so that we could survive and live longer. And with that comes ceremony and we do dancing, we sing. All of our songs are about rain. The rain’s coming. It’s coming. It’s thundering. It’s lightning. You can see it. The clouds are gathering. They’re coming this way from the north. The south. There’s songs with all those words and all of them have something to do with rain or snow, all the time. Whether it’s a Buffalo dance, whether it’s a butterfly social dance, whether it’s kachinas. Whether it’s clowns. It all has to do with rain. It all has to do with snow, because we need that water to live. Because without it. There’s no life. Our own people, the Hopi people, are losing their faith in prayer and they are losing faith in who they are. They are losing their identity of who they are, and even the language is diminishing. And without that holistic wholeness, everything is off balance for the culture and tradition and the way of life and how we grow corn today, or how we grow food in general. How we used to do.

Gina: Do you have any advice you could share for young people who want to engage more with their cultural practices?

Nadine: All I can offer you is from my own life. This is the only thing I can speak from and about. It’s very hard to concentrate and decide what’s cultural, traditional culture and what’s not.

First of all, you need to know who you are. You need to know where you came from. What tribe are you from? Who are you? What is your language? What is your tradition? Who do you come from? What is it that they do? What are they known for? Who are you? You have to find that identity for yourself and know who you are first before you can move forward in your life.

The second thing is if you know your language, that’s great because that’s going to distinguish you. Because you’re Native American and if you don’t know your language, you might think about wanting to know it. Because if you don’t know it, you’re going to be like any other person in the world. As a Native person you have to find some kind of cultural identity for yourself. If it’s not language, then it might be the song. It might be dancing. But you have to find yourself.

“As a Native person you have to find some kind of cultural identity for yourself. If it’s not language, then it might be the song. It might be dancing. But you have to find yourself.”

The third thing is you have to be physical. In order to live a long, strong life, in your young life, you have to have physical activity. Today our young people have tablets and phones and they’re sitting there, they’re not being active. And then we have all this junk food. Nobody eats any of what they grow anymore or anything like that. Everything’s for convenience, but it’s not healthy. So you have to pay attention to yourself to be strong in life so that you can endure a long life.

You have to have faith in prayer. It’s something that was given to all people of all color was worship and faith and the power to endure our lives in this world. The Creator gave that to all of us in various ways so that we could survive on earth and how to live. But it had to be in harmony, and faith in the Creator. And so you have to always do that, no matter where you are, if you ever get in trouble. Pray. ‘Cause they’ll answer. Your prayers will be answered. And that’s all I can offer. And see, that’s all anybody has, this prayer.

Gina: Thank you for sharing that. My last question is, what are your hopes and visions for your family, your Hopi homelands, your people?

Nadine: My vision is to continue living what I know and what I’m supposed to be doing. My vision is that my family, my children, will carry that forward from the teachings that I’m trying to give them. I’m hoping that it’ll continue. My vision is to stay as connected as I can for my family to continue to practice and remember who they are. And carry everything that we’ve learned forward because if it’s not carried forward, everything will disappear, and we’ll be like everyone else.