As I pattered through the desert, a time when my mother called me shíyázhí, her little one, I felt the most connected to the kéyah/jewed (land). Each wandering step drew me closer to the heart of the desert, where every rock and chirping cactus wren held a piece of her story. I credit much of my curiosity about environmental science and ecology to those early years of running around and sharing palo verde branches with the cactus wren.

I am Kinyaa’áanii, born for Áshįįhí. My parents are from the Navajo Nation with my mom from the Wide Ruins area and my dad from Dilkon. I was born in Flagstaff, Ariz., but I grew up outside of Tucson, sharing a fence with Tohono O’odham’s Shuck Toak District. As a Native and Indigenous person I believe it is important to acknowledge that I am not of these lands, I am a visitor. I was taught to show the utmost respect and reciprocity towards things that are not one’s own. One of the ways I practice this teaching is through mindfulness. By occupying another’s land I carry these teachings with me to move around in the world in a good way.

There’s a phrase in my language, “Tó éí ííńá át’é,” which expresses the idea that water is sacred because of its ability to give life. To be mindful of one’s water usage is a responsibility all desert dwellers hold. However, there was a time when this responsibility was neglected. One question I have had for as long as I can remember was how the Santa Cruz River is called a river if it’s mostly dry throughout the year. I believed that this was the way it had always been.

The Black Hill, also known as Sentinel Peak or “A” Mountain. Credit: Shecota Nez.

The View from the Black Hill

In 105-degree heat, I ventured out to a well-known spot called Sentinel Peak, also colloquially known as “A-Mountain”. The journey up the hill involves driving through the Menlo Park neighborhood, which is considered the oldest neighborhood and the birthplace of what we call Tucson. The name “Tucson” is derived from the O’odham phrase “Cuk Ṣon” (pronounced: Tshoo’ook Sone), which translates to “(at the) base of the black (hill)” or simply “black base”, referring to that fact that Sentinel Peak’s base is considerably darker than its summit. This area served as a place the Tohono O’odham lived, loved, and stewarded since time immemorial.

With the power of the Santa Cruz River, generations of O’odhams raised families and crops. The Tohono O’odham have solidified themselves as arguably the most prolific agricultural society on Turtle Island. The power of the Santa Cruz River was used to engineer canal systems to water the crops. The Santa Cruz River was a source of nutrient-dense topsoil to feed the crops. Their main food sources include tepary beans, squash, and corn, which were farmed every year, in addition to harvesting food from desert plants and animals.

While on the peak of the Black Hill I can see the homely downtown center, historic Menlo Park neighborhood, bustling Mercado San Agustin, and St. Mary’s Hospital. From the view, the river is difficult to identify amongst suburban sprawl, which is surprising when comparing the view to a photo from the early 1900s. My eyes attempt to carve out the flow of the river, but my efforts are fruitless. In the photo, my eyes follow its wide and meandering path as my mind wanders to a time when otters and beavers roamed the banks of the river. It was through conversations with tribal leaders and conservationists, that I got to learn more about the surrounding community and where the river has gone.

A historic image from 1904 shows a lush Santa Cruz River wrapping around the base of the Black Hill. Public Domain Image from Arizona Historical Society.

Modern-day view of Tucson from the Black Hill in June 2024. The Santa Cruz River is no longer visible. Credit: Shecota Nez.

A Previous Chapter

A common misconception about deserts is that they are lifeless, unappealing, and harsh. However, the Sonoran Desert was and still is the most biodiverse desert in the world. There are many reasons for this, but in my region, the Santa Cruz River and the years of Indigenous stewardship are the most influential.

According to Luke Cole from the Sonoran Institute, from time immemorial to about 1910-1920, sections of the river flowed year-round while others flowed seasonally. This is due to the geographical nature of the bedrock beneath. Sections in Tucson and Nogales have bedrock levels that are closer to the surface, which contribute to the perennial flow in those regions. Additionally, the river curves around Martinez Hill which applies inertia to the flow so that its nutrient-dense soil overbanks into a mile-wide flood plain that is Cuk Ṣon.

Prior to the arrival of settlers in the mid-1500s till forced assimilation in the 1600s, the Tohono O’odham occupied this area and surrounding areas as their summer homes. During this time, the People planted their summer crops, harvested saguaro fruit (Ha:sañ Bak), rested, and participated in ceremonies.

To learn more about the historical conditions of the Santa Cruz, I spoke with Sally Pablo, Vice Chairwoman of the Tohono O’odham Nation’s San Xavier District, who recounted interviews with Tohono O’odham elders about their memories of the Santa Cruz River. According to Pablo, elders recalled large swathes of riparian ecosystems along the river, which included Gila topminnow, Southwestern river otter, Sonoran beaver and the Colorado River toad, some of which are now either endangered or extinct. O’odham elders reminisced on their youthful summer days under the watchful canopy of mesquite, cottonwood, desert willow, and marshy grasses along the river. Many reveled about the Great Mesquite Forest, which covered seven square miles of mesquites and cottonwoods with some of the oldest trees reaching heights of more than 65 feet, and four feet in diameter. The roots from these trees were able to reach the groundwater and thrive for hundreds of years, until their life was quickly drained from them.

During the late 1600s, the Spanish and subsequently Mexican settlers began to occupy the area. All parts of the ecosystem were threatened, including aquifer levels, geographical elements, riparian animals, forests, and Indigenous stewardship. In the grand lifetime of the Santa Cruz River, it was only relatively recently when excessive water pumping began to threaten its life. Settlers began to grow crops such as citrus and non-native cotton, which are not suitable for the natural desert climate because of how much water they require. Ranching became a major economic activity, due to the available land, but tending to large herds of cattle requires a significant amount of water and food production. Traditionally, the O’odham used the natural floodplain and constructed canals near the river to irrigate their crops. Inefficient water usage resulted in the dry riverbed seen today.

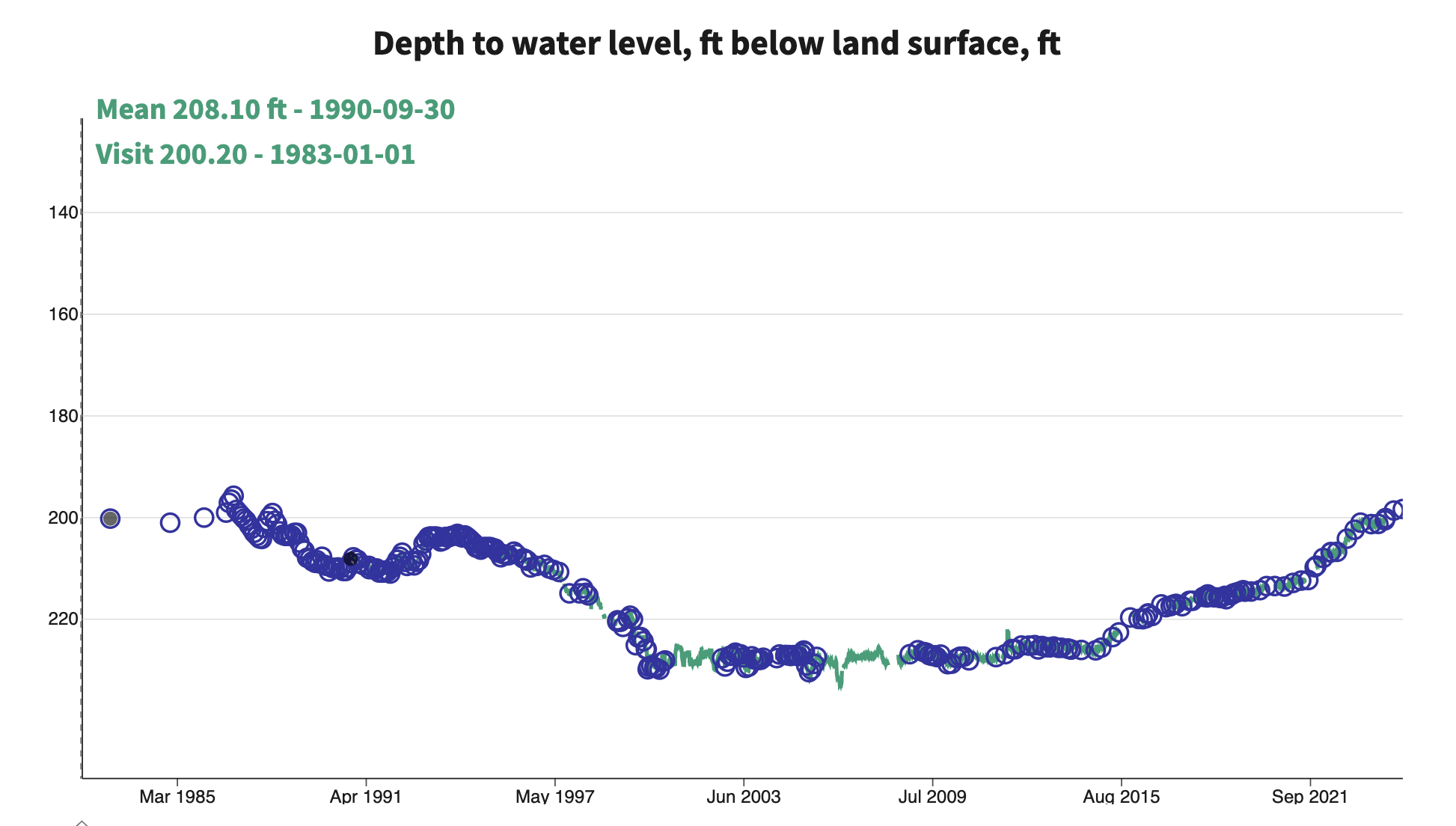

Today, water issues are directly connected to tribes’ access to water, with a Tier 2a shortage declaration for 2023 mainly affecting Arizona tribes. Poor water management practices have created lasting effects on the region’s hydrology, and these effects are now being compounded by the pressures of climate change.

Graph showing changes in Tucson’s groundwater table from the 1980s to today. With improved water management practices, the groundwater table is slowly rising. Data from USGS.

A Changing Climate

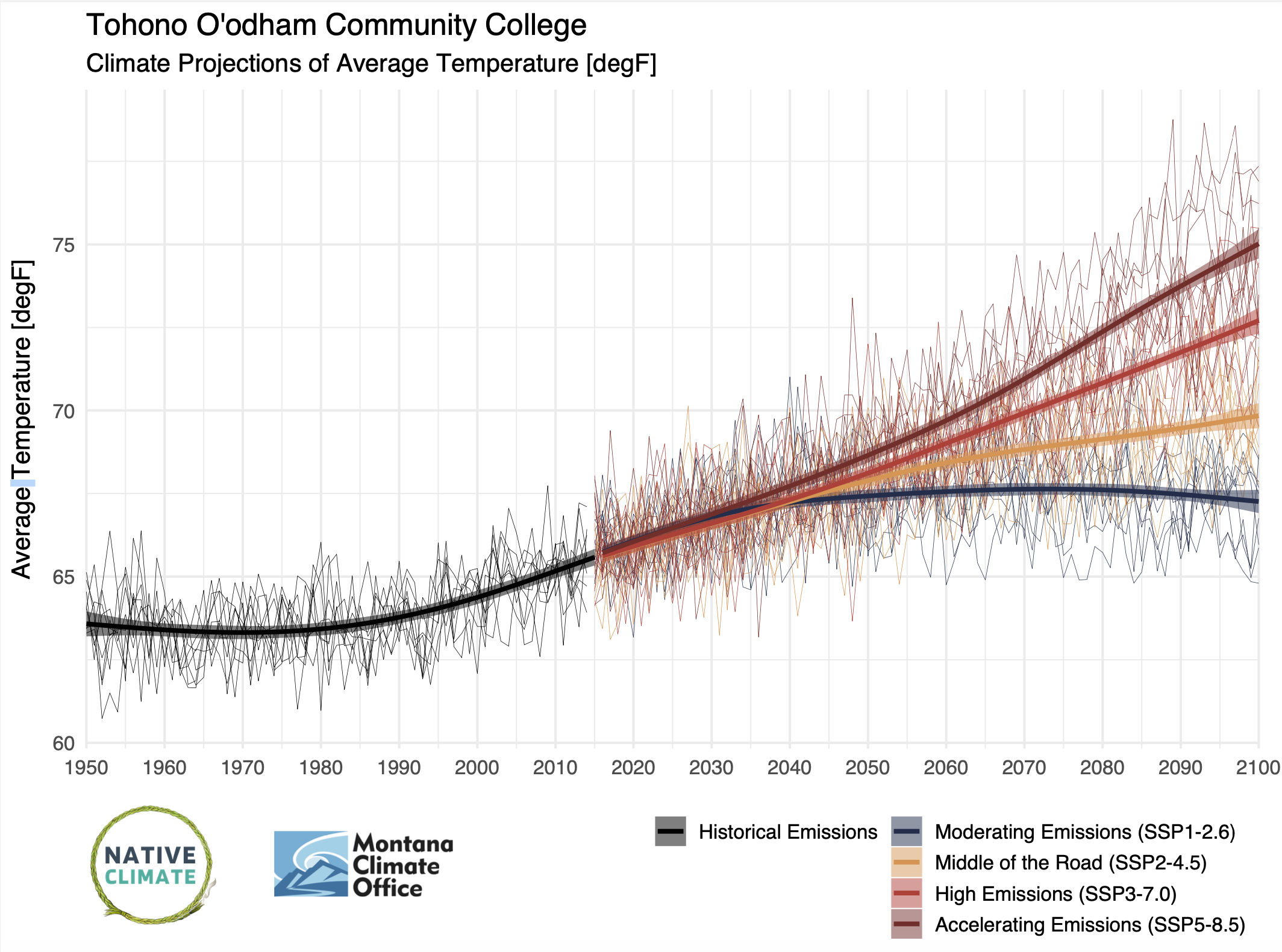

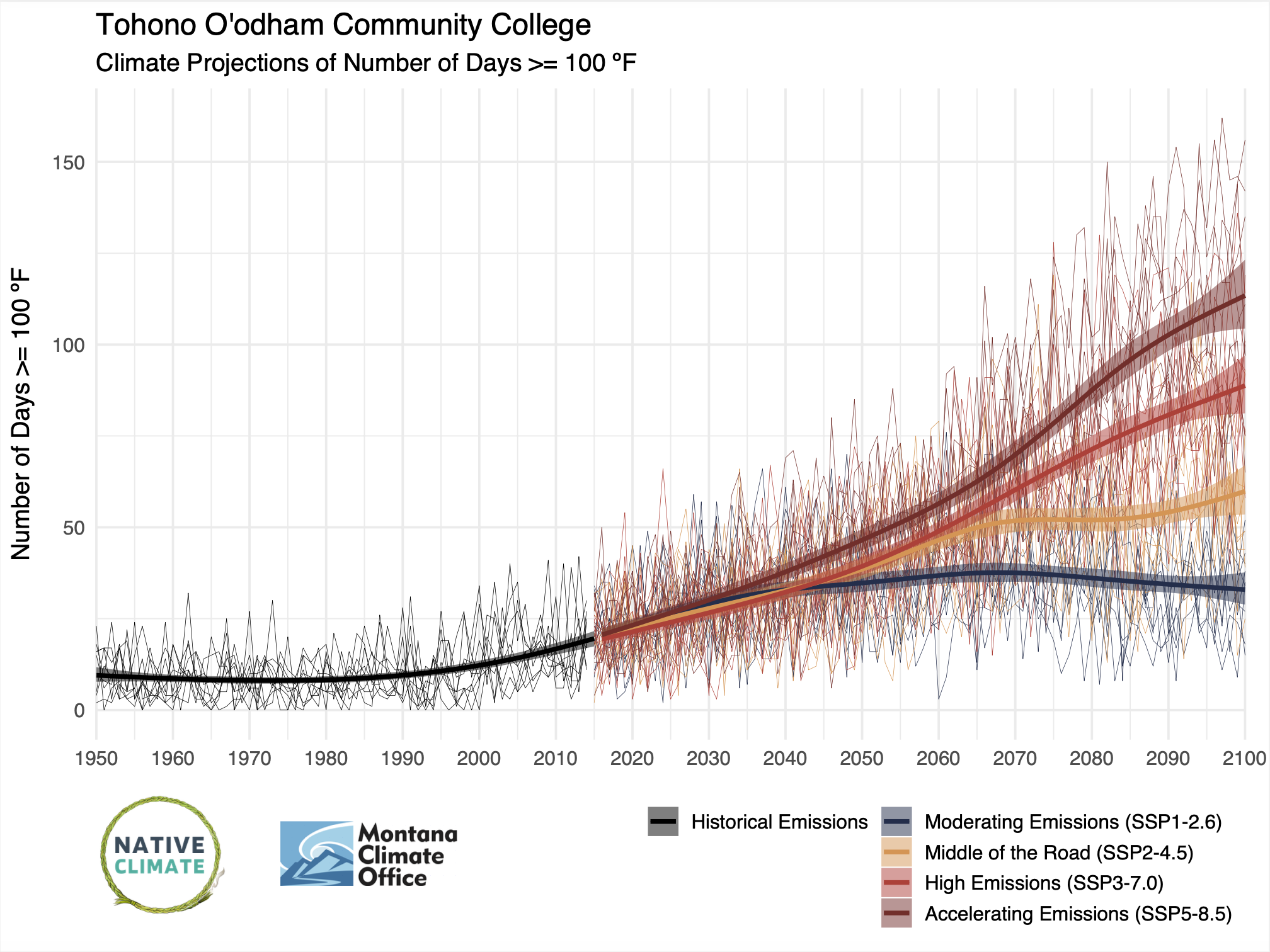

As global climate change warms, the Santa Cruz River and surrounding area will be affected by warming as well. Climate scientists study the effects of climate change across various emission scenarios — moderating, middle of the road, high, and accelerating–to ensure there is accuracy in climate predictions. Future projections for the Tohono O’odham Nation do not show an overt change in precipitation in regards to annual precipitation, season precipitation, average precipitation on wet days, and number of wet days. However, predictions about temperature—including average daily temperature, the number of days with temperatures at or above 100°F, and the number of frost-free days—show a positive correlation across all emission scenarios. This trend aligns with the first day of the growing season starting earlier and the last day of the growing season occurring later in the year.

Climate records and future projections of average temperature for the Tohono O’odham Nation and surrounding region, 1950-2100. Credit: Native Climate.

Climate records and future projections for number of days exceeding 100F for the Tohono O’odham Nation and surrounding region, 1950-2100. Credit: Native Climate.

Several concerns come up when considering how these predictions will affect the environment and livelihoods in the region. The shift in growing seasons can affect traditional and ceremonial O’odham practices associated with harvesting. Additionally, more emphasis on planting drought-resistance native vegetation is important to fight the heat without exacerbating the water usage. In the future, the benefits of consistent precipitation will likely be undercut by the rising temperature, because there will be a higher rate of evaporation from the soil. Due to this phenomenon natural recharging of the aquifer is less likely. There will be more of a reliance on man-made recharging efforts, such as using reclaimed water to revive the river.

Reviving a River

The Tohono O’odham Nation and the City of Tucson have completed river restoration projects to help bring water back to the Santa Cruz, including a project called the Wa:k Hikdan and another called the Heritage Project. While the execution of each project differed, they shared a common goal: fostering a healthier river.

Heading about 10 miles south from the Black Hill, the San Xavier District of the Tohono O’odham Nation is home to about 1,200 Tohono O’odham citizens and the Wa:k Hikdan site. Here, conversations with the busy Vice-Chairwoman of the San Xavier District Sally Pablo allowed me to learn more about how the Wa:k Hikdan project came to life and the effects it has had on the community.

Due to the excessive water usage by the City of Tucson, the Tohono O’odham Nation filed a lawsuit in the early 1980s to obtain structured water rights. In the end, the Southern Arizona Water Rights Settlement Act, the amendment Arizona Water Settlements Act, and the Arizona Water Protection Fund aided in the construction of the Wa:k Hikdan.

The project planning committee surveyed several areas before beginning construction in 2002. The plan was to pump water from the Colorado River with help from the Central Arizona Project to the San Xavier District to fill the section of the river.

The District spoke with elders at the time to understand what their goals should be. Elders spoke of the shade and coolness the mesquite and cottonwoods provided. Now in 2024, the Wa:k Hikdan is bearing witness to the revitalization of the community. Under the canopy of mesquite leaves and cottonwoods, youth workshops, weddings, festivities for elders and so much more take place. The Tohono O’odham are able to reconnect with the water and land.

Vice-Chairwoman Pablo mentioned that the City of Tucson sent representatives to tour the Wa:k Hikdan before construction of the City’s project, the Heritage Project, began. The Heritage Project, finished in 2019, is located along the Chuck Huckelberry Loop between W. Starr Pass Rd. and W. Silverlake Rd in Tucson. Luke Cole from the Sonoran Institute spoke about the new water reclamation technology used to recharge this portion of the river, and the encouraging results that they have seen.

“The water is so clean that we are seeing the return of endangered fish species,” Cole said. “People are coming back to the river. Wildlife is coming back to the river.”

While visiting the site I did not see any fish, however I could hear the sound of water and insects chirping. As I looked out over the tall marshy grasses, I became eager to see how this project will impact the Tucson community. Cole warned while restoring the river will benefit the overall Tucson community, there is concern of gentrification of the Menlo Park, Barrio Hollywood, and other historically Black, Brown, and Indigenous neighborhoods along the river.

“When the Santa Cruz River was dried up and stinky, where did all of our Black, Brown, and Indigenous neighborhoods in Tucson get pushed? Right up against the river. ” Cole said.

A view of the Santa Cruz River in the City of Tucson’s Heritage Project. Credit: Shecota Nez.

Looking Backwards to Move Forward

In these past few weeks, I have learned so much about my home. Now when I go outside to water my mom’s plants I see everything differently. The hearty palo verde, the towering saguaro, the gentle giant mesquite, and the versatile creosote are scattered around my childhood home as they always have been, each teaching me a valuable lesson about how to thrive in a desert. Supplemental help has also come from the Tohono O’odham community, in the form of my neighbors, my classmates, and Vice-Chairwoman Sally Pablo. Without their help, I would not understand the true relationship between land and community. Even so, my question from childhood has been answered. Plainly, now I know the dry, crackly riverbed is only a recent development for the Santa Cruz River. The river has lived a long life with so much left in store. Thankfully, the restoration projects are helping the river stay resilient against a changing climate. The return of the tall marshy grasses, and people returning shows us that the river never fully died and with continued Indigenous stewardship efforts, and mindful water usage the Santa Cruz will live on.